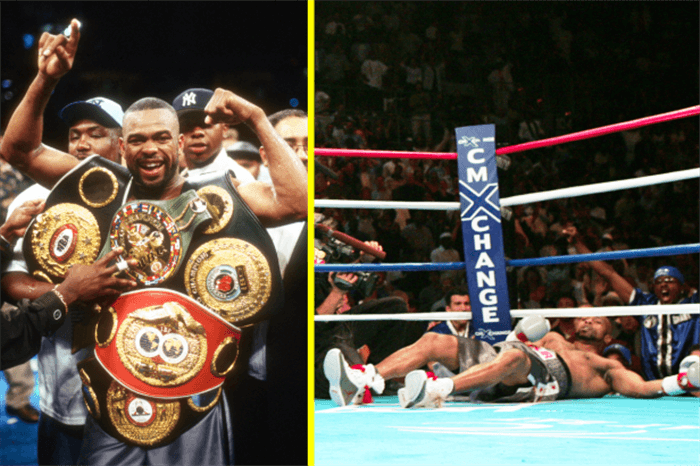

It has often been said of the great Roy Jones Jr that had he retired the night in 2003, when he won the WBA heavyweight world title by outpointing John Ruiz, he would continue to be remembered as the finest of all fighters.

There was perhaps also a time in his career, when he remained at his remarkable peak, that the American proved the most untouchable any fighter ever had.

Groomed for greatness since before he had turned professional at middleweight – he was voted the best boxer at the Seoul ’88 Olympics despite being denied the gold medal by the most controversial of judges’ decisions – his swift rise to the top took none by surprise.

There were also few more aware of his greatness than Jones Jr himself, raving about his talents and ruing the opposition who proved so incapable of presenting him with a test.

When he won his first world title – the IBF middleweight championship – in 1993, the great Bernard Hopkins was his opponent and won just four of 12 rounds.

After defending it once against Thomas Tate he moved to super-middleweight, where the similarly great James Toney was the IBF champion and was knocked down in the third round in the process of an even more one-sided defeat.

Jones Jr was introduced to boxing by his father, with whom he later became estranged. Growing up on a farm in Pensacola, Florida, he was also subjected to the toughest of regimes by his dad.

“My father would holler and get physical, whatever it took,” he said in 1988. “He had a plastic pipe. He’d hit me with it all the time. Leave a welt. Sometimes I’d cry. He’d tell me to shut up.”

There were times Jones Jr appeared to barely lose a round. In 1996, so certain was he of victory over Eric Lucas that he played a full minor league basketball match beforehand. In 2002 against Glenn Kelly he put his hands behind his back, stuck out his chin to tempt Kelly to punch and him and then landed an explosive right hand on the Australian’s chin to knock him out.

His only setback came in March 1997 when, after a competitive start to their WBC light-heavyweight title fight, in the ninth round Jones Jr succeeded in forcing Montell Griffin to one knee. The referee Tony Perez was slow to intervene as Jones Jr landed two further punches and Griffin, perhaps capitalising, collapsed to the canvas, ensuring Jones Jr’s disqualification.

Little over four months later, he got his revenge by stopping Griffin inside a round.

Eight years after Jones Jr had been denied in Seoul, Antonio Tarver earned Olympic bronze in Atlanta. He had also established himself a fine professional light-heavyweight and was pushing to challenge Jones Jr when the world’s finest fighter instead chose to challenge Ruiz on an evening when he had a 34lbs weight disadvantage.

On perhaps Jones Jr’s finest night, the charismatic Tarver confronted him at his post-fight press conference to demand they fight. “Before I retire, if I only fight one more time, his ass is mine,” Jones Jr eventually said. “Don’t think I’m going to let him off.”

It was seven weeks before their date at Las Vegas’ Mandalay Bay that terms were finally agreed. Until then there had been discussions for a further heavyweight fight with either Evander Holyfield or Corrie Sanders, which contributed to the 34-year-old Jones Jr, in preparation for Tarver at light heavyweight, having so little time to lose the 24lbs of muscle he had gained.

Jones Jr significantly reduced his food intake and adopted an intense cardiovascular training regime to do so; by the time he weighed in he therefore looked unhealthily and uncharacteristically drawn. He had previously spoken of how much he had struggled to return to the light-heavyweight limit and, in his pre-fight dressing room, told HBO that he felt ‘about a seven’ out of 10.

It took until the fourth round, against an opponent fighting with conviction, for Jones Jr – unusually slow to start and struggling with his timing – to start to perform anything like in the way that had become expected of him, and by the middle rounds it was Tarver who had become hesitant. A strong seventh regardless precipitated further rounds in which Tarver dominated as he had during the first and second, and ultimately a competitive fight until the 12th and final round. One judge scored a draw at 114-114; the others scored 116-112 and 117-111 in Jones Jr’s favour.

When he was unable to secure the lucrative heavyweight fight he sought with Mike Tyson, Jones Jr, previously insisting with the words ‘one and done’ that he was about to retire, instead got tempted into a rematch with Tarver at light-heavyweight in May 2004.

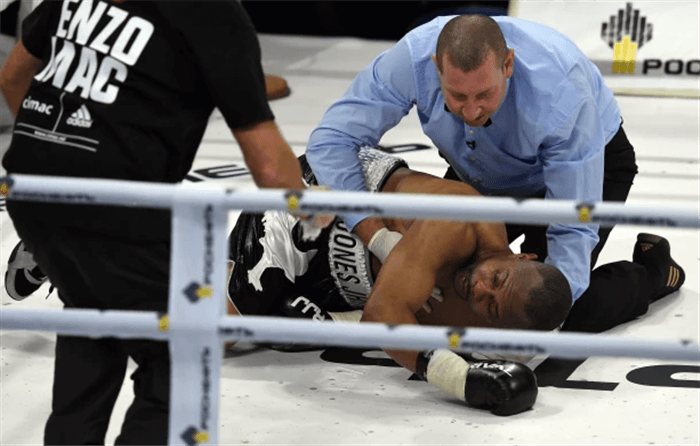

A minute into the second round at the same venue he was then caught by an explosive left hand. After proving his resilience in their first fight he collapsed on to his back – his head and shoulders fell under the ring’s ropes – returned to his feet on the most unsteady of legs at the count of nine, and was waved to defeat by referee Jay Nady.

By then 35 and having demanded so much of his body, Jones Jr – his reflexes and athleticism deteriorating yet still fighting with the style that demanded they remain a strength – had fought on for too long. Widespread disbelief and disappointment naturally followed that most dramatic of ends.

The legacy he had worked so had for was then threatened by him being stopped by Glen Johnson and outpointed by Tarver. Three successive defeats marked the start of the undignified, wider total of 10 for a fighter who would likely be remembered as the finest of all if he had quit while he was ahead.