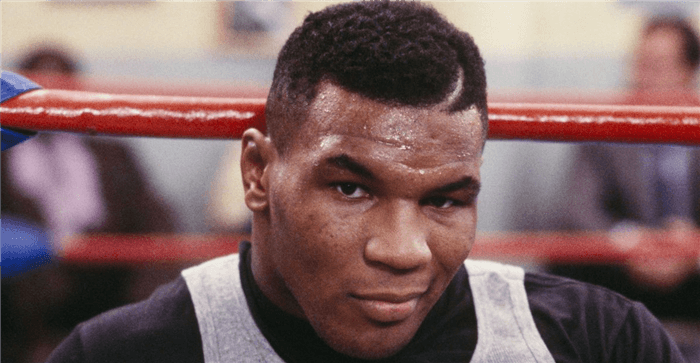

Mike Tyson, the 21-year-old heavyweight champion of the world, sat naked on a metal folding chair, fuming, desperate and angry, choking back tears. There were three of us in the room: Tyson, trainer Kevin Rooney and me. “Everything in my life was too good to be true, wasn’t it?” said Tyson. You would recognize the voice, the same one that comically menaced Zach Galifianakis in the first Hangover movie, only with fewer miles on it. You can hear it. “It was just too good,” he said. “Now my life is so screwed up.”

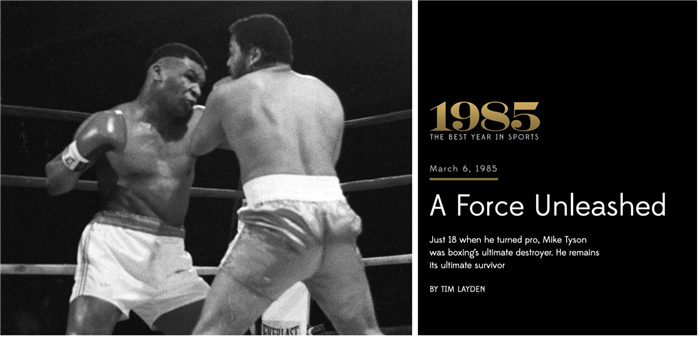

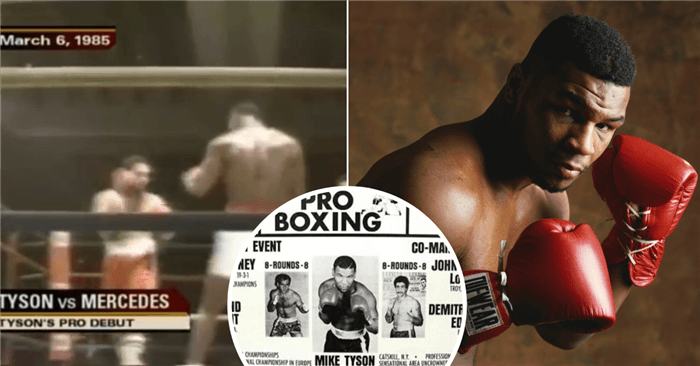

There was a notebook in my right hand, a tape recorder beneath it, running. Tyson had stormed out of the ring after a desultory sparring session and hissed that he wasn’t talking today, but here he was, talking just the same. Rooney waved me into the room. I was a familiar face. Over the course of the previous 27 months, as a writer for the Albany Times Union, I had traveled frequently to Catskill, to Atlantic City and to Las Vegas as Tyson rose from Knockout Curiosity to heavyweight champion to the precipice of Full-blown Freak Show, and on most of those trips I had at some point sat and talked privately with Tyson. Uncertainty always hung in the air; Tyson could give you grunted single syllables or the history of boxing in the 1960s.

But even by those standards, this moment was different. Thirty-nine days later, Tyson would fight Michael Spinks to unify the heavyweight title, but here there was already a battle on for his soul and, more to the point, his growing fortune. Tyson’s co-manager, Jim Jacobs, had died two months earlier (Tyson’s mentor and legal guardian, trainer Cus D’Amato, had been gone since November of 1985), throwing open the door to all manner of takeover strategies. As Tyson sat unclothed and ranting, his first wife, actress Robin Givens, was staying in the Catskill Victorian home in which Tyson had lived with D’Amato and D’Amato’s longtime companion, Camille Ewald, since 1980. Rapacious fight promoter Don King was holed up in an Albany hotel. Bill Cayton, Jacobs’s longtime partner, was in New York City, ostracized, but scrapping. “Everybody is pulling at me, this way and that way,” said Tyson. “Everybody’s got their hands out, waiting for something from me. I don’t need them. I don’t need anybody. I could go fight you in the street, outside this building, and somebody would pay me a million dollars for it.”

“Something drastic is going to happen soon,” Tyson said. “Screw the world.”

When the session ended, I walked down to the street and climbed into my ’83 Honda Civic. It was a dizzying time in my life. My wife was 36 weeks pregnant with our first child, and I was sitting on job offers from two New York City newspapers (the customary path to career advancement in 1988), either of which would mean leaving upstate friends and family behind while dragging my wife and baby to an unfamiliar new home. My work in covering Tyson had helped get me noticed by potential employers, yet here I sat by the curb with a tape full of his insecurities and pain to transcribe and regurgitate for anyone to read. I felt guilty, but not too guilty not to make sure the recorder had successfully captured the conversation. I raced four exits up the New York State Thruway and banged out a story that led the sports section the next morning and, even in the pre-Internet age, was quickly snatched up and disseminated around the world. Any Tyson news was big in those days.

But Tyson was also right. Things were going to change. His rise to greatness had been a wild, exhilarating sprint that tapped into a primal bloodlust, and not just his, but the public’s, too. That was ending, right here and now, already fading into history before my paper’s press run began. And we may never see its kind again.