Not to say I’m old, but my hips function like the Tin Man in rust mode and my earliest sports memories are of leaning over the big walnut radio set with my ex-boxer father listening to the Friday Night Fights: Archie Moore, Sugar Ray Robinson, Carmen Basilio, Gene Fullmer, Jersey Joe Walcott, Rocky Marciano.

The old man loved Willie Pep, because Pep was a master of not getting hit. I always wanted to be like Willie Pep, but when we boxed I got hit — early, often and hard. The old man was not a believer in coddling kids.

I was more interested in doing the blow-by-blow from ringside, which is perhaps why I ended up at ringside, trying to write about the fight game as well as those old-time announcers described it on the radio, ending up with the occasional blood spatter on my laptop.

That’s how I found myself on Father’s Day, watching a series of fights featuring a boxer my old man admired more than any other: Muhammad Ali’s two bouts against Sonny Liston early in his career and the epic Rumble in the Jungle against George Foreman, when Ali used every bit of guile, cunning and skill he had to knock Foreman out in the eighth round.

If you’re weary of overhyped modern sports events, when even the greatest athletic feats are lost in a deluge of gambling ads, highlight reels and broadcasters shouting “unbelievable” every 15 seconds, I strongly recommend delving into the past, as I did with the Canadiens 1993 Stanley Cup run and with Ali Sunday evening.

You don’t have to be a boxing fan to be in awe of what Ali accomplished in his 1964 fight against Liston. He came in as a cocky, loud-mouthed 22-year-old, a huge underdog against a fighter who made lesser boxers quake and left the ring as what he proclaimed he was — the greatest in the world.

What Ali did was simple. He did not get hit. It’s why boxing can be an art form, while mixed martial arts is a bar fight.

On that chaotic evening in Miami, Ali was an unhittable butterfly with a sting. Liston stalked him like a bull after a matador and with about as much success. Then, at the end of every round, Ali would abruptly change his tactics, stand his ground, and throw punches from every angle, connecting in combinations too quick to follow.

Even in the fifth round, with his vision clouded by stinging liniment that may have been on Liston’s gloves, Ali remained unhittable. He was almost fighting blind, slipping punches that could have killed him, and he still couldn’t be touched.

When Ali dominated the sixth round, throwing more and more of those crackling combinations, the fight was over. Between rounds, doctors bought Liston’s explanation that he had dislocated his shoulder and stopped the fight.

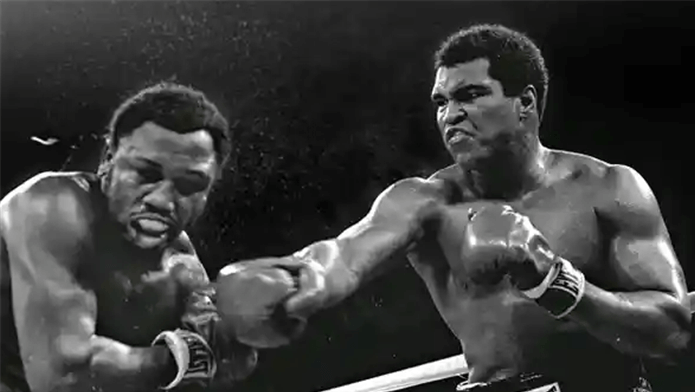

Ten years later in the Rumble in Zaire, Ali was slower than the unhittable Cassius Clay of 1964, which does not mean he was slow. He danced for two rounds, leaned on the ropes for the next five, and still managed to throw stinging combinations to remind the younger Foreman who was boss.