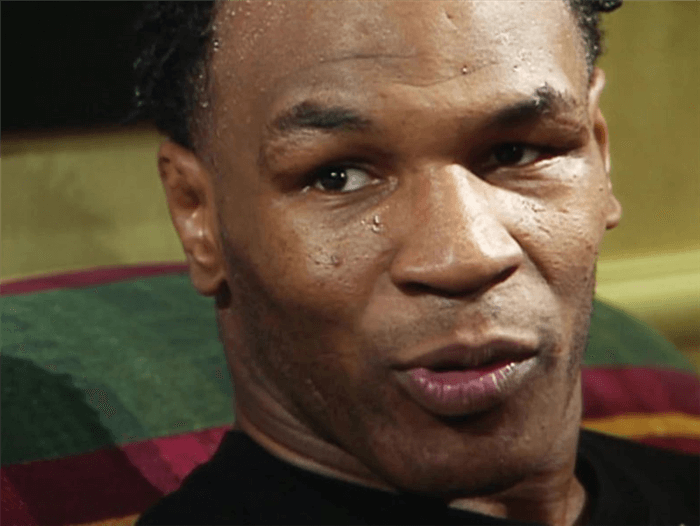

“When I first met him at the press conference I was so wound up – I’d have fought him, then and there,” says Julius Francis two decades later

Mike Tyson’s first fight in Britain, 20 years ago to the day, was a whirlwind of police sirens and imprisoned gangsters, with a boxing match briefly thrown in. It was anarchy, Tyson-style, during the weirdest and most chaotic period of his career.

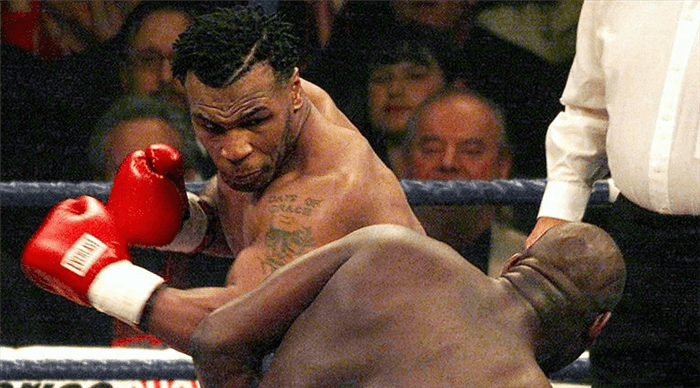

Tyson defeated Julius Francis in Manchester 29 days into the new millennium, flooring him five times in a brutal two rounds, but the fight itself was when order was restored to a controversial few weeks. For the four minutes that it lasted, at least.

“The only thing I’d change? Not the training, not the money, not the atmosphere. The only thing would be the outcome,” Francis told Sky Sports two decades later. But he felt like part of a minority who wanted the fight to happen, at the time.

Tyson, aged 33 and no longer the world heavyweight champion, was slowly slipping into total disarray. He had messily divorced Robin Givens, had lost two fights to Evander Holyfield (in the second of which he notoriously bit off a chunk of his rival’s ear). He returned by viciously yanking at Francois Botha’s arm before knocking him out, then chinning Orlin Norris after the bell resulting in a no contest.

Tyson had been imprisoned twice, most notably serving just under three years for rape. Campaigning groups and politicians rallied not to let Tyson come to the UK but Home Secretary Jack Straw granted him special dispensation. The fight was on.

“It was put to us that, with Tyson coming to England, the only person he could box would be the British champion. That was Julius Francis,” said his trainer Mark Roe.

Francis was given little chance, with 21 victories from 28 fights, and attracted ridicule when he accepted sponsorship from Piers Morgan’s Daily Mirror to put the newspaper’s logo on the bottom of his boots. The implication being that he would inevitably tumble and display the logo. Francis literally sold his soles.

“It was about making his bank account a bit bigger. He had to do it,” Roe remembered, adding that it was the brainchild of Francis’ manager Frank Maloney (now Kellie).

“I’d never had this level of scrutiny,” Francis said. “It was new to me. Sponsorship and newspapers? I wasn’t interested. I didn’t meet Piers Morgan but he said some disparaging things about me.”

What if Francis bumped into the Daily Mirror’s former editor today?

“I’d have a bit of banter with him!”

It was a light-hearted subplot to Tyson’s arrival, which was a more macabre affair. Heathrow was jam-packed, protestors and supporters awaiting, when he touched down in the same Concorde as George Michael. The boxer was flanked by police offers, the pop star was mercifully untroubled.

“It was a big issue, but not for me. If you go to prison you have paid your debt to society,” Francis said about the controversy of Tyson’s arrival to the UK. Francis had also been inside but was rehabilitated after finding boxing.

“He was made out to be a wild animal, a wild dog. That wasn’t fair.”

An increasingly hostile Tyson had become obsessed with the Kray Twins, the east end mobsters. He claimed at the time: “Reggie wrote me a letter in prison when I was at the lowest point of my life. I was very grateful for that.”

Plans to visit Reggie Kray in hospital were shelved but Tyson, whose entourage dominated the luxurious Grosvenor Hotel during his stay, ventured unannounced and unprepared to Brixton in south London causing mass hysteria.

“If I was not fighting him, I would have been one of the people in Brixton because I was a fan,” Francis said.

Francis was marched into battle by a brass band before Tyson’s trademark entrance, so simple and untamed it is still haunting to this day.

Tyson landed a left hook inside five seconds. Francis was floored twice in the opening round, the Daily Mirror logo getting its first unveiling. With the second round less than a minute old, Francis had crashed to the canvas a further three times. It was over.

“I fought Tyson as a man and came out as a man,” Francis said.

“Some of the fights Tyson had later were against bigger names and better fighters than me, but he blew past them like a puff of wind. Tyson didn’t even hit Bruce Seldon but he fell over and was scared like a frightened chicken. At least I fought the guy, even if he beat the crap out of me, at least I had a row with him.

“It’s nice to have respect, and I genuinely know that Tyson respects me.

“To have my name linked alongside Tyson’s is amazing. I have stories to tell when my grandkids ask me one day.”

The rage of Tyson in Britain would not end in Manchester. Six months later at Hampden Park in Glasgow he bulldozed through the referee as he knocked out Lou Savarese.

Francis reflected 20 years on: “Tyson’s story is inspirational. We both came up as kids with similar paths on different sides of the world. We went through the same struggles. We found boxing.

“He was still a child at 20 years old [when he became world heavyweight champion]. Lots of things that happened to him would never have been allowed to happen today. Wider society had a part to play in his downfall.”

Today Tyson has mellowed as an author, a film star and a one-man stage show. Francis works in security and with kids from the same background as himself. They forever remain a small part of each other’s stories.