What if you overcame a serious illness to go on to win an Olympic medal? Could a writer or filmmaker decide to tell your inspiring story without consulting you? Or do you “own” that story and control how it gets retold?

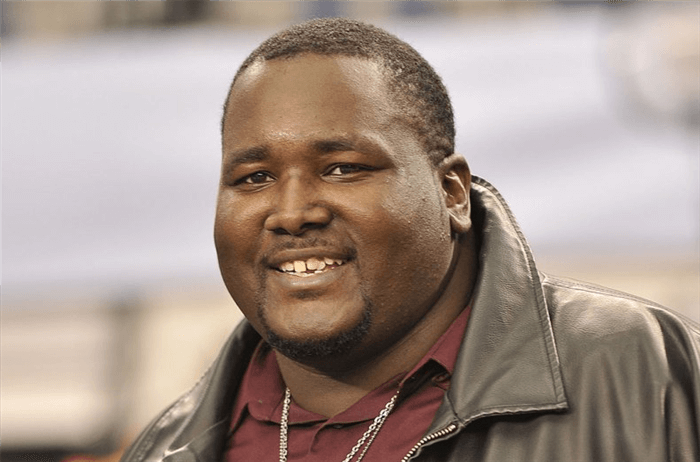

Michael Oher, the former NFL player portrayed in the 2009 blockbuster “The Blind Side,” has sued Michael and Anne Leigh Tuohy, the suburban couple who took him into their home as a disadvantaged youth.

In his official complaint, Oher claims that through forgery, trickery or sheer incompetence, the Tuohys enabled 20th Century Fox to acquire the exclusive rights to his life story.

The Tuohys, Oher continues, received millions of dollars for a “story that would not have existed without him,” while he claims that he received nothing.

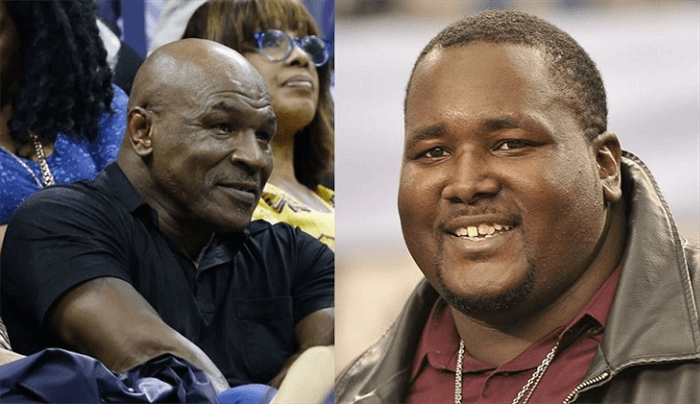

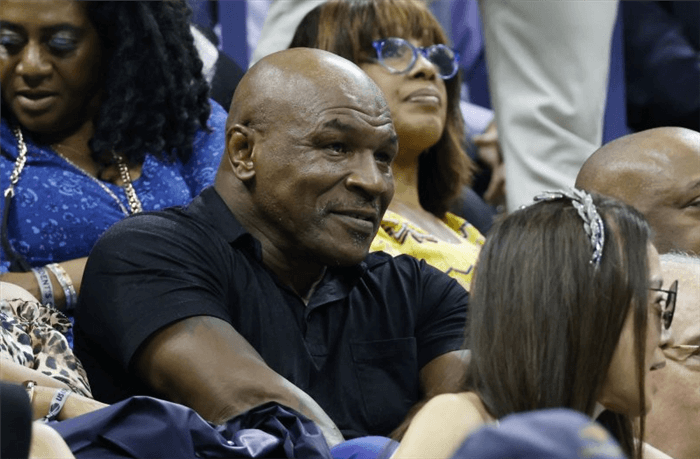

Just a year earlier, former heavyweight champion Mike Tyson was similarly incensed when he learned that Hulu had created a miniseries dramatizing his career without seeking his permission.

“They stole my life story and didn’t pay me,” Tyson charged in an Instagram post.

Oher and Tyson – not to mention countless influencers and wannabe celebs – share the conviction that they own, and can monetize, their life stories. And given regular news stories about studios buying “life story rights,” it’s not surprising to see why.

As law professors, we’ve studied this issue; our research shows that there is no recognized property right under U.S. law – or the laws of any other country of which we are aware – to the facts and events that occur during someone’s life.

So why are Oher, Tyson and others complaining? And why do publishers and studios routinely pay large sums to acquire rights that don’t exist?

No monopoly on the truth

In most states, the commercial use of an individual’s name, image and likeness is protected by the so-called “right of publicity.” But that right generally applies to merchandise, apparel and product endorsements, not facts and actual events. So you can’t sell a T-shirt with Mike Tyson’s face on it without his permission, but writing a book about his rise to fame is fair game.

In the U.S., the freedom to describe historical events is rooted in the free speech clause of the First Amendment, and it’s a fundamental principle that no one – whether it’s a news agency, political party or celebrity – holds a monopoly on the truth.

The law doesn’t sanction the invasion of privacy, so an investigative journalist who uncovers some unsavory detail of your past can’t publish it unless there is a legitimate public interest in doing so. Nor does it condone the dissemination of false information, which can lead to defamation lawsuits.

The First Amendment, however, does allow authors and film producers to truthfully depict factual events that they have legitimately learned about. They are not required to receive authorization from or pay the people involved.

The origin of life story ‘rights’

Film producers, however, are accustomed to paying for the right to repackage or use existing content.

Copyright licenses are required to commission a script based on a book, to depict a comic book character in a film and to include a hit song on a movie soundtrack. Even showing an architecturally distinctive building often requires the consent of a copyright owner, which is why the video game “Spider-Man: Miles Morales” had to remove the Chrysler Building.

Along with these other rights and permissions, Hollywood studios have paid individuals for their life stories for at least a century.

Yet, unlike copyright clearances, life story deals do not involve the acquisition of known intellectual property rights. Life story “rights” are not rights at all. Instead, they bundle together a set of contractual commitments: the subject’s agreement to cooperate with the studio, not to work on a similar project, and to release the studio from claims of defamation and invasion of privacy.

By packaging these commitments under the umbrella of “life story rights,” studios can signal to the market that they have acquired a particularly juicy story.

For example, Netflix’s quick deal with convicted fraudster Anna Sorokin, the subject of the popular streaming series “Inventing Anna,” seems to have deterred competing adaptations of Sorokin’s story.

What’s more, the acquisition of life story rights has become so common that it is viewed, in many cases, as a de facto requirement for film financing and insurance coverage and thus part of the standard clearance procedure for many projects.

Exceptions don’t make the rule

As always with the law, though, there are exceptions.

Notably, the producers of the 2010 film “The Social Network” did not obtain the permission of Facebook founder Mark Zuckerberg before dramatizing the origin story of his company. In moving forward with the project, they risked a defamation or publicity suit by Zuckerberg and others depicted in the film. But their gamble paid off: Zuckerberg,

while critical of his depiction, didn’t sue.

Nevertheless, other subjects who have been depicted in dramatic features without their authorization have sued to recover a share of the profits.

Silver screen legend Olivia de Havilland, for example, sued FX Studios for briefly depicting her in a miniseries about Hollywood rivals Bette Davis and Joan Crawford. She won at trial, though an appeals court reversed her victory, citing the producers’ First Amendment rights.

Lawsuits can even be brought when the characters’ names and story details have been changed. U.S. Army Sgt. Jeffrey Sarver, the bomb-defusing expert who inspired the Oscar-winning film “The Hurt Locker,” sued the film’s producers for violating his right of publicity. He lost.

Lawsuits like these are not the norm. But many producers hope to get ahead of a flimsy lawsuit and bad publicity by acquiring nonexistent rights.

History is in the public domain

Ultimately, there is nothing wrong – and much that is right – with paying individuals to cooperate with the production of features about themselves. Doing so can convey respect toward the subject and make the production go more smoothly.

But the fact that life story acquisitions have entered the popular consciousness has spurred the widespread belief that any portrayal of a factual series of events entitles those depicted to a lucrative payday. This expectation increases production costs and the risk of litigation, thereby deterring otherwise worthwhile projects and depriving the public of meaningful content that is based on true stories.

What could be done about this situation?

One idea that we’ve written about would prevent right of publicity laws – the basis for many life story lawsuits – from being used against works that convey ideas and tell a story, such as books, films and TV shows.

Perhaps the most important thing that can be done, though, is educating people that they don’t have a right to cash in on every description of the events of their lives.