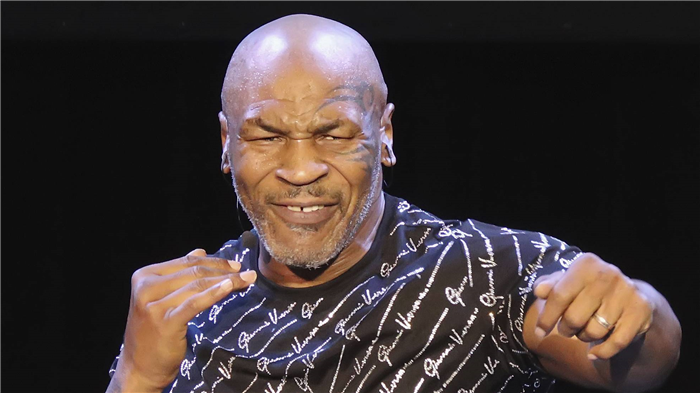

“I’m always crying,” says Mike Tyson, in a voice so low and meek. “I should have done better than what I am. My addiction. What I did with my family. The way I dealt with my finances. The way I dealt with my relationships with other people. The way I dealt with myself.” He looks at me, eyes shining. “There’s a whole bunch of stuff but I don’t let it ruin my life. It can’t ruin my life.”

Even the outline of the MGM Grand can be seen from the bottom of Tyson’s street, where the boxer nearly two decades ago bit a chunk out of Evander Holyfield’s ear in a fit of rage. At the time, Tyson was the youngest world heavyweight champion in history and had just been released from prison for the rape of Miss Black Rhode Island (he maintains his innocence).

Then came Tyson’s first bankruptcy, which was followed by a lost decade during which he drugged himself with marijuana and antidepressants, sipped from $US3,000 bottles of Louis XVIII cognac, and smoked a continuous stream of Marlboro cigarettes with cocaine in place of the tobacco. He started to consider suicide during that time after one of his daughters, Exodus, moved in with her.

Those days are over. Crazy Mike has become Suburban Mike…

Tyson keeps himself in check through Islam and veganism, and has given up bingeing on his favourite tipples of Bacardi and blueberry brandy. Even his pet tigers are gone, leaving only the boxer’s 100 or so homing pigeons as his non-human companions.

I arrive at Tyson’s home forewarned by a list of pre-interview conditions: Mr Tyson will not discuss politics, Mr Tyson does not want a female journalist, Mr Tyson would like to see the questions.

“When you look at me now, I’m just a simple guy,” Tyson reassures. “I mean, there’s always a part of me that wants to go back, that’s the addict part. But I know what the repercussions of that would be. Really, I premeditate what I do in my life now, because of that. It was very difficult to make this choice. But I don’t want to be the guy who has the big scandal and I have to go to my daughter’s tennis class and it’s all over the school.”

And he worries about his daughter Milan getting older, her future on the tennis court, even the men she’ll date. “I’ll be very serious when it comes to that,” he warns. “I don’t want her dating guys like me.”

Tyson leads me outside, past his sparkling lap pool, to see his 100 or more homing pigeons, all cooing softly on the roof of his garage, next to a coop the size of a two-bedroom flat. He picked up the interest as a kid, from a group of violent thugs in Brownsville.

“I thought it was so cool that these rough, bad people liked birds,” he recalls. “They’d just train them to fly around. It made them very happy. And I loved it. My whole life, the only time I stopped with the pigeons was when I went to prison.” He adds, sadly, “I never get into trouble when I’m paying attention to my birds.”